WHEN ALL IS STILL

Rachel Monosov

Rachel Monosov questions power structures and the meaning of freedom in her multidisciplinary practice. Her background as a Soviet-era child, and her constant migration around the globe since 1991, fuels her focus on the relationship between body and nation-state. Over the past decade, Monosov has treated the political sphere with a poetic hand; using the power of beauty much like nationalist propaganda does: to hide the monster underneath.

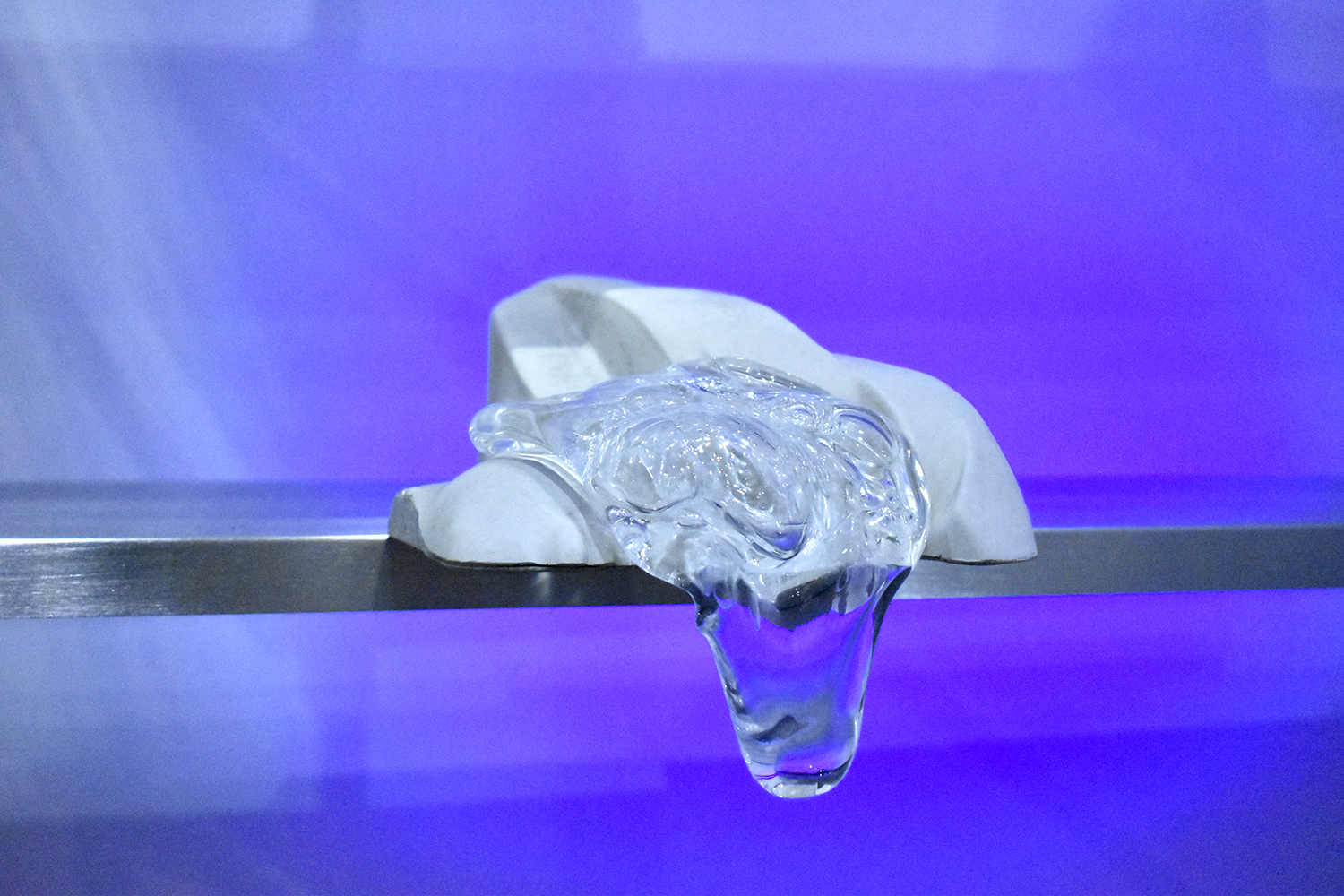

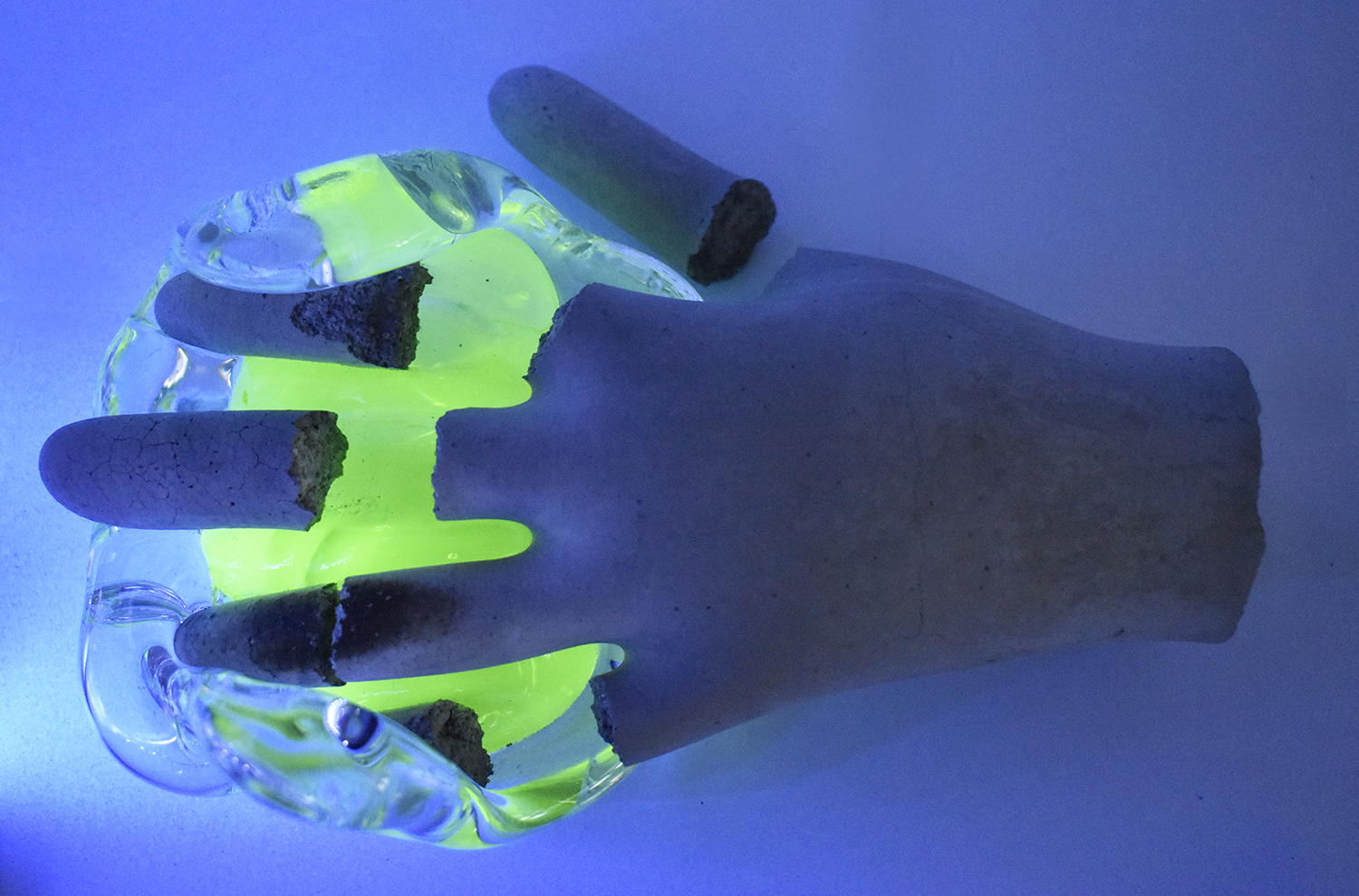

For Art Basel Hong Kong 2024, Monosov presents new cement and uranium glass sculptures. The combination of materials and loaded symbolic cues speaks to identity and socio-economic history, weaving the artist’s autobiography into the geo-political moment. The sculptures are replicas of Soviet monuments, particularly those of the Socialist Realism era. Male and female heads decapitated from their bodies are given new meaning by the uranium glass elements that cover, divide, or support them. An eagle’s wing lies on top of a glowing green pillow whilst its head is constrained within a fluorescent globe. A hand, having at some point held the mighty five-point star, is conserved within the warm sphere of a display dome, and another holds a glass drop of tears frozen in time.

Uranium glass, a unique radioactive material, was no longer used after the Manhattan Project. Although it is safe to handle and live with, its characteristic green glow is reminiscent of an ominous reality. The lingering specter of fear built by the proliferation of nuclear arsenals during the Cold War is imprinted on the collective consciousness and perpetuates a cycle of conflict and control that distorts our perception of power and security – an influence that continues to shape people’s decisions, opinions and voting behavior decades after its fall.

The artist points to the relationship between social realism and the nexus of nuclear weapons, connecting these systems of control to contemporary warfare. Through opposition, the cement and glass create a visual poem of man-made ideas which could, and did, bring darkness to humanity. Socialist Realism played a role in shaping public perception within the Soviet Union, producing official accounts starkly different from the lived experiences of those affected. Today, the role of nuclear weapons as potential catalyst for unprecedented devastation looms large, adding an extra layer of urgency to these artistic narratives.

The accompanying two-channel video work fast forwards us into a post-nuclear future. A character plays the artist, the creator, who tirelessly carries the heavy cement sculptures, but breaks them at will, stepping out of the suspended disbelief demanded by these objects. She breaks them for artistic freedom, which was, and today still is, robbed from artists by oppressive governments. She breaks the whitewashed representation of a much darker reality. While this rebellion is taking place, on a second screen, where the objects lie broken and still, they offer a backdrop, a landscape, for the endurance of one of the few creatures which could survive a nuclear disaster.

Lastly, as we consider the fragile timeline of our existence within the universe of WHEN ALL IS STILL, we encounter a marble and bronze installation on the floor of the booth. The marble slab, in the standard size of a grave, is engraved with the words: “Almost replaced by the smell of red roses, I can still smell what is burnt.“ On top is a bronze sculpture donning a multiplicity of estranged noses exhaling visible vapor, with each breath perpetually living the engraving they sit upon.

Still, bringing the argument full circle, the beauty in these works leaves the door open for the potential of stillness and reflection; maybe even for peace.