We Are Almost There

Rachel Monosov

Installation, We Are Almost There, Tarble Arts Center, Eastern Illinois University, 2019

Installation, Freedom In The Clouds, Tarble Arts Center, 2019

Installation, Vox Populi, Tarble Arts Center, 2019

Installation, 1972, Tarble Arts Center, 2019

Installation, We Are Almost There, Tarble Arts Center, Eastern Illinois University, 2019

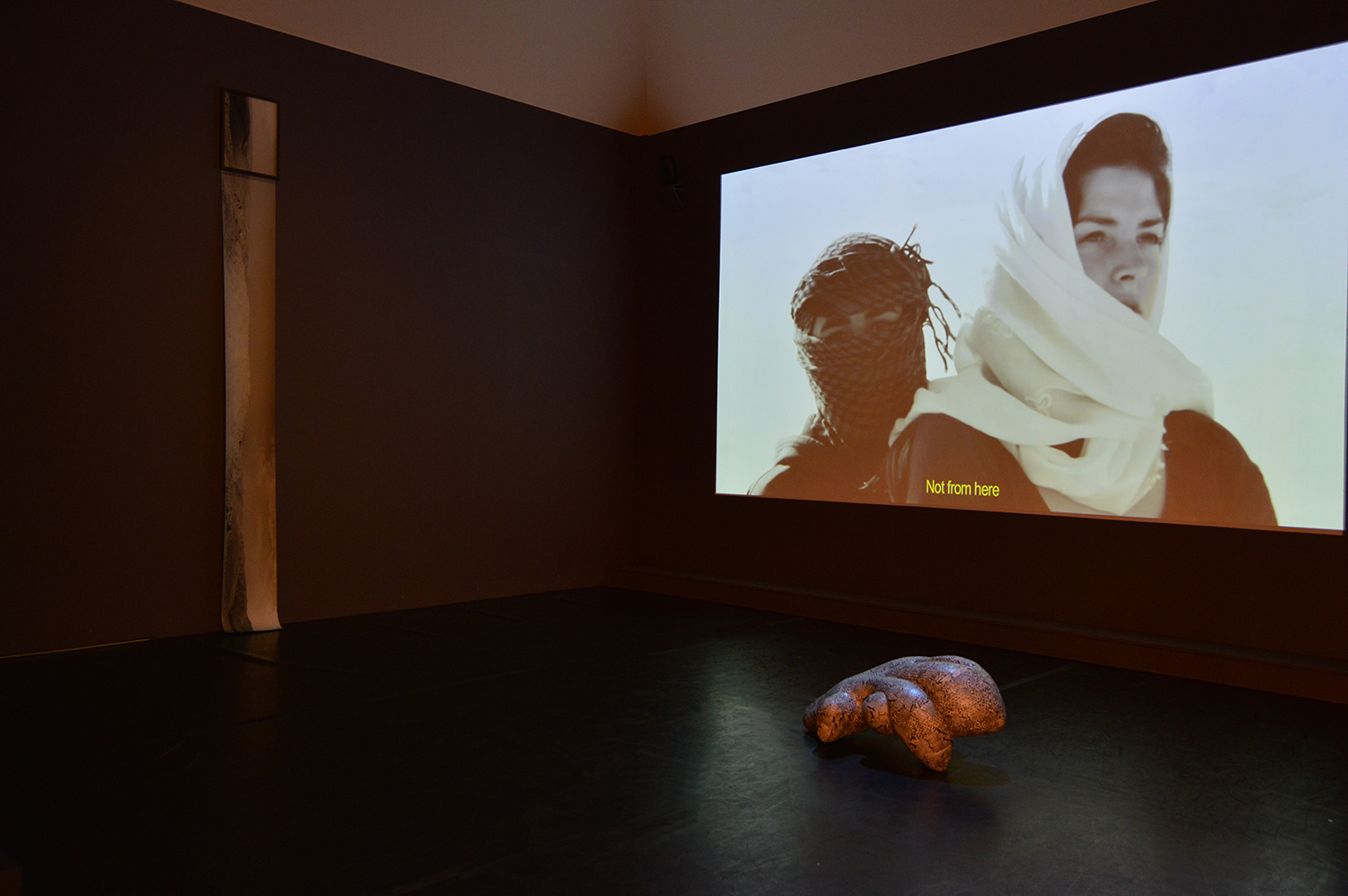

Installation, The Visitor, Tarble Arts Center, 2019

Installation, Left, Right, Right, Right, Tarble Arts Center, 2019

Installation, Melodica, Tarble Arts Center, 2019

Rachel Monosov

We Are Almost There

Tarble Arts Center

October 24, 2019 – January 6, 2020

INTRODUCTION by Catinca Tabacaru

In 2014, Rachel Monosov made The Visitor, a video work which looks at the body as citizen, an evolution from the artist’s prior work which considered the body as primarily female.

In The Visitor, a character played by Monosov, lands in the Judean desert. The soundscape of the film clonks and chimes with otherworldly oddity, while this out of place traveler surveys the local fauna with curiosity, as an explorer who is seeing it for the first time. She moves about the land with the help of a Bedouin boy. “Do you speak English?,” she asks as he leads her across the sand on his donkey. “She’s not from here, she’s from Belgium,” we hear a voice explain, the cameraman perhaps. In fact, Monosov was raised in Israel, but moved away several years before making this film. Knowing these details adds a political layer to the work. What does it mean to return to one’s homeland and feel like they no longer belong?

Rachel Monosov followed this work in 2015 with another video work, Freedom In The Clouds. The film’s aesthetics – a futuristic ultra-white, almost sterile, yet lush environment – present uniformed botanists wearing lab coats and sharp-edged bangs tending to the plants of an enclosed rainforest. A flag bearing images of clouds accompanies the video as if to declare a new state, a heterotopia of sorts. In fact, the work combines footage from two locations: the botanical garden in Jerusalem where the artist’s mother works, and Tropical Island, a sunny, sandy resort south of Berlin built inside an old Soviet airplane hangar. As a direct follow up to the sense of estrangement that is conveyed in The Visitor, this work could lead a viewer to presume a dissatisfaction on Monosov’s part with the state, or at least the politics, of her home nation.

This relationship between body and state takes an even stronger hold of Monosov as global politics continue to shift rightward, and this state of affairs confronts viewers upon entering We Are Almost There at the Tarble Art Gallery. We encounter the mechanical repetition of a portrait 30 times. Monosov expects that for some this visage – a long face, prominent chin, narrow and straight nose with a low bridge, light eyes, fair skin, and straight blonde hair – will represent a superior type of human. And these “some” tend to hold power; power over movement of bodies across borders, power over freedom of expression and election, power over the ability to love openly. One of these portraits faces left, the others right. The work is titled Left, right, right, right, right and was made in 2018, a time when the “free borders” across the European Union were starting to feel less and less free depending on the tone of one’s skin.

There are many works in this exhibition that address the links between race, power, migration, and freedom, and all are layered with the artist’s singular aesthetics. Monosov has regularly explored these themes over the past five years and has set her subjects within constructed environments, which function pursuant to their own sets of laws. Her work, set within these fictional parameters, opens opportunities for the expansion of thought and discussion around them.

We live in a time when a new generation coming to power is inheriting a corrupt and hateful past. But, as the show’s title suggests, it is also a time when hope and change are at our fingertips. Are we almost there? Is the world ready to embrace the arrival points of Monosov’s utopian ideas? In the 2017 photographic installation, 1972, in which we see a Jewish woman and a Zimbabwean man be married, build a home, and vacation freely in a war-torn Rhodesia when black nationalists were fighting to win over the lands, Monosov and Admire Kamudzengerere call out “the real happiness of a family,” as the light at the end of a time and space tunnel where their relationship would have led to persecution. And, as early as 2013, before the transgender movement carved its place into our collective consciousness, Monosov offered Is There No One To Unite Us?, a sculpture donning the hermaphroditic body of a snakeskin creature.

Turning from themes to method, it is significant to note that Rachel Monosov’s working media span the gamut as much as her topics envelope the globe. From performance, to cinema and photography, to sculpture, she has both a studio and non-studio practice, producing in non-spaces, and collaborating with other creatives and local communities to make site-specific and time-responsive works.

She made Vox Populi in Zimbabwe during the contested 2018 presidential election, the first following the resignation of long-time president Robert Mugabe. Surrounded by hope, disillusionment, and fear, Monosov and I both bore witness to a country whose people participated in a democratic election, many for the first time, only to be robbed of its result by Zanu PF, the same political party who had oppressed the country under Mugabe’s rule for decades prior. With the help of collaborators – including fellow artists, both Zimbabwean and international; the CTG Collective; local organization Dzimbanhete Arts & Culture Interactions; and the neighbors who continued to care for the work after its installation and through a bush fire that turned the ground black – Monosov installed a billboard in the middle of the rural landscape 20-minutes outside of Harare, declaring the Latin phrase “vox populi” (the voice of the people), and printed swag with the same slogan which was freely distributed to both the local people and visitors from the city. With only goats and a few small homes in viewing distance, the “voice of the people” referenced by Monosov was effectively heard by only a very few. This work reaches far beyond the borders of one African nation. Its layers reveal themselves: a research into the meaning of words; a questioning of what democracy is today; a mimicry of contemporary campaigning techniques; a conundrum; a silent protest.

When I was asked to write this introduction, I had to contend with the fact that for the past decade I have been perhaps the closest advisor to the artist and observer of her work. The previous paragraph refers to our fourth trip together to Zimbabwe (our first was in 2015). Through our long-term engagement with the country, we have been able to watch first-hand its transition from the increasingly restrictive years of Robert Mugabe’s presidency, to the hope for freedom and prosperity that is felt today. It goes without saying that it was also our love for Zimbabwe’s people and its earth that kept bringing us back, and further so, Monosov’s collaborations with artist Admire Kamudzengerere, an example of which is present here in the performance-based photographic work 1972.

Rachel Monosov and I co-founded the CTG Collective long before I opened the Catinca Tabacaru Gallery in New York City and Rachel designed the Gallery’s Harare space, which we later built with a team of local builders and the Zimbabwe-based collaborators mentioned above. This ongoing project has led us to travel the world together, exploring new ways of seeing life and art.

1972 is a work that embodies the union of pursuits present in this making of art outside the comforts of one’s studio or home country. I will let Kathleen Bickford Berzock’s compelling essay within this catalogue tackle the complexities of the work, but I want to touch briefly on its relationship with Monosov’s film Melodica, which was made just prior to 1972. Shot in the concrete modernist architecture of the House Van Wassenhove in Belgium and structured around Lucas Cranach the Elder’s painting The Golden Age, the film could not be more Western, more distanced, from the setting of a pre-Zimbabwe Rhodesia. And yet, the Oligarchy of Melodica—of three melancholic, spoiled youths in the belly of Europe’s wealth—are more tied to the apathy and gluttony that has condemned parts of the African Continent over centuries than is commonly admitted. It is the same force that is seen in corrupt elections, in racialized immigration laws, and in the occupation of territory at the price of people’s lives, homes, and history. It is all connected, and Rachel Monosov’s work reminds us of this universality, of our shared obligation, but also offers a moment of respite, a hope for a time when there is no tragic news to report and we’ll all be able to relax and listen to the seashells.