Hagoogtir/Unveiling

Najaax Harun

Najaax Harun, trapped, 2024, acrylic and oil pastels on canvas, 100 × 100 cm

Within one woman, a lineage of women is entangled.

Every woman carries within her all the eggs she will ever have, by the time she is four months in the womb. Literally connecting her existence to that of her ancestors, each of us has spent five months within our grandmothers’ wombs, linking us to the collective experience of womanhood and its burdens.

The physical body of a woman holds a sentiment of confinement.

“If only I were a man” are words echoing through generations, capturing a pervasive yearning for liberation.

Najaax Harun, stitched on one another, 2024, acrylic and oil pastels on, canvas, 100 × 100

Stitched on one another opens a dialogue on motherhood within a patriarchal framework. It examines how society imposes immense pressure on both mother and daughter, testing their bond under the weight of expectations.

Like two bodies sewn together, they move in unison, often unable to confront the looming shadow cast behind them—the unspoken demands and constraints of their roles. The tension lies in their struggle to grow apart, to assert individuality, without unraveling the delicate thread that binds them, a metaphor for the profound challenges of navigating identity and autonomy within a system that conflates womanhood and sacrifice.

Najaax Harun, The Oblation, 2024, acrylic and oil pastel, 300 × 150 cm

Oblation often symbolizes a sacrificial act or offering meant to appease deities or spirits, reflecting deep-seated rituals and beliefs.

This imagery raises a poignant question: Are we all merely offerings, awaiting our turn in the grand, often enigmatic, ritual of existence? The juxtaposition evokes a reflection on the nature of sacrifice and our place within it.

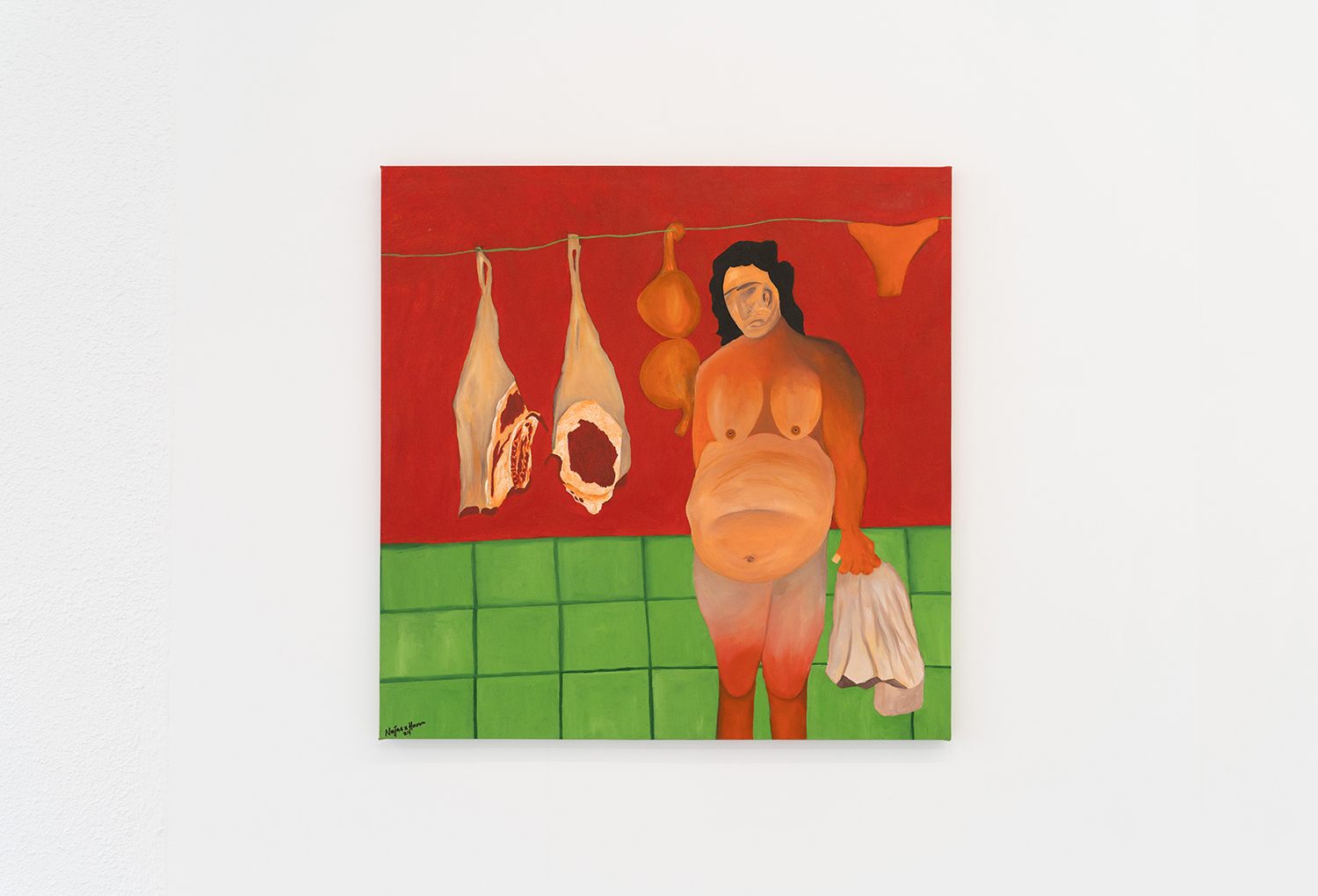

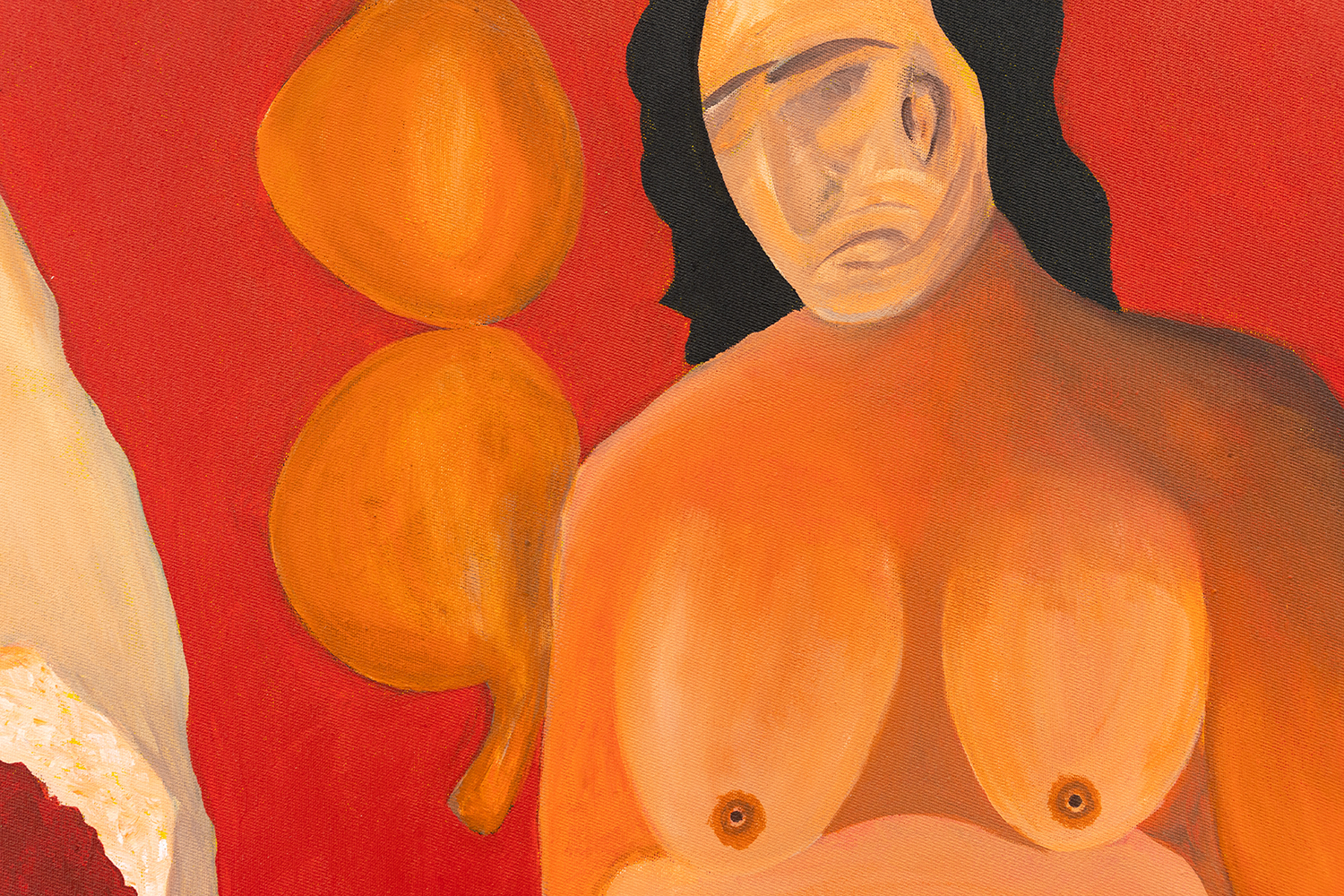

Najaax Harun, Fresh meat, 2024, acrylic and oil pastels on canvas, 100 × 100 cm

There is a well-known Somali saying I grew up hearing: “Jidh dumar wa hilib bisil,” meaning “a woman’s body is like fresh meat.” This phrase was often spoken as a warning, suggesting that when I ventured out, I was akin to fresh meat among predators. In darker moments, it served as the final justification for harm inflicted on women—implying that the fault lay with her. How could she have been alone when the harm occurred? What was she doing there? Didn’t she know she was fresh meat, walking unguarded? This saying reflects the deep-seated victim-blaming embedded in cultural narratives that hold women accountable for harm done to them based on their gender, beauty or social standing.

Najaax Harun, passing on honor, 2024

acrylic and oil pastels on canvas, 50 x 100 cm

A shadow of a woman passes the mantle of so-called honor to another, embodied in the form of a veil. This act suggests that a piece of fabric becomes the defining measure of a woman’s worth and dignity. The veil, not the woman herself, becomes the symbol of her value, and without it, she is denied the illusion of respect that society bestows upon those who conform. The veil is not merely cloth; it is a mechanism of control, reinforcing the belief that a woman’s honor is external, conditional, and rooted in submission to societal norms

Najaax Harun, straight path, 2024, acrylic, oil pastel, 90 × 110 cm

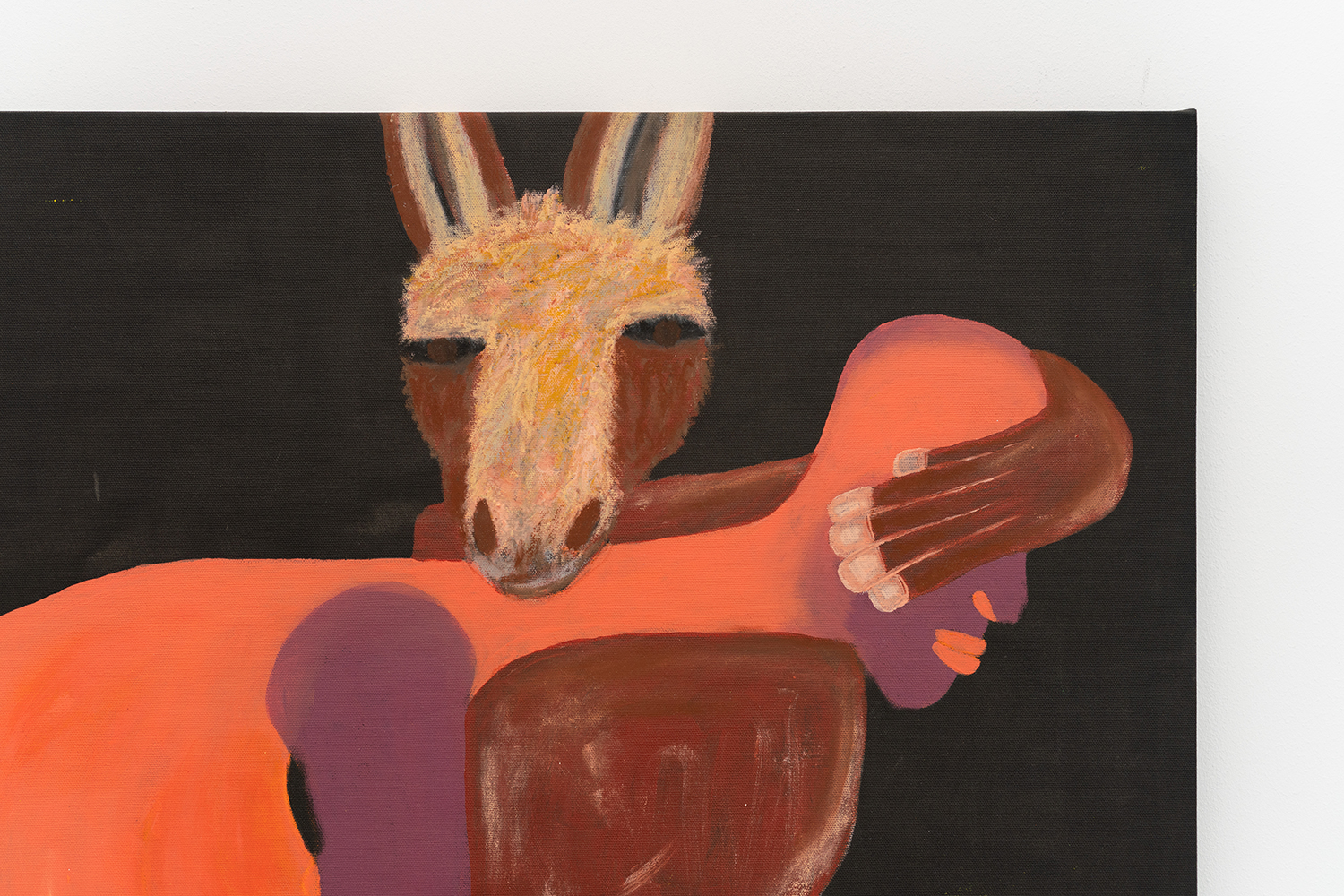

Straight path draws inspiration from the parallels between guiding a group of humans and leading a group of donkeys.

In my community, to direct a donkey, we affix two cardboard pieces on each side of its eyes, narrowing its vision to the path ahead, ensuring focus, discipline, and a singular direction. This practice, while seemingly mundane, serves as a satirical commentary on how communities not only control animals but also navigate social interactions with one another. In retrospect, I see echoes of this in my own upbringing and education—where, though not literal pieces of cardboard, systems of belief and education shaped and constrained perception, guiding me along predetermined paths

Najaax Harun, Sept. 2024.

Najaax Harun, lost in translation, 2024, acrylic, oil pastels. 100 × 85 cm

Najaax Harun, powerlessness, 2024, acrylic and oil pastels on canvas, 100 × 100 cm

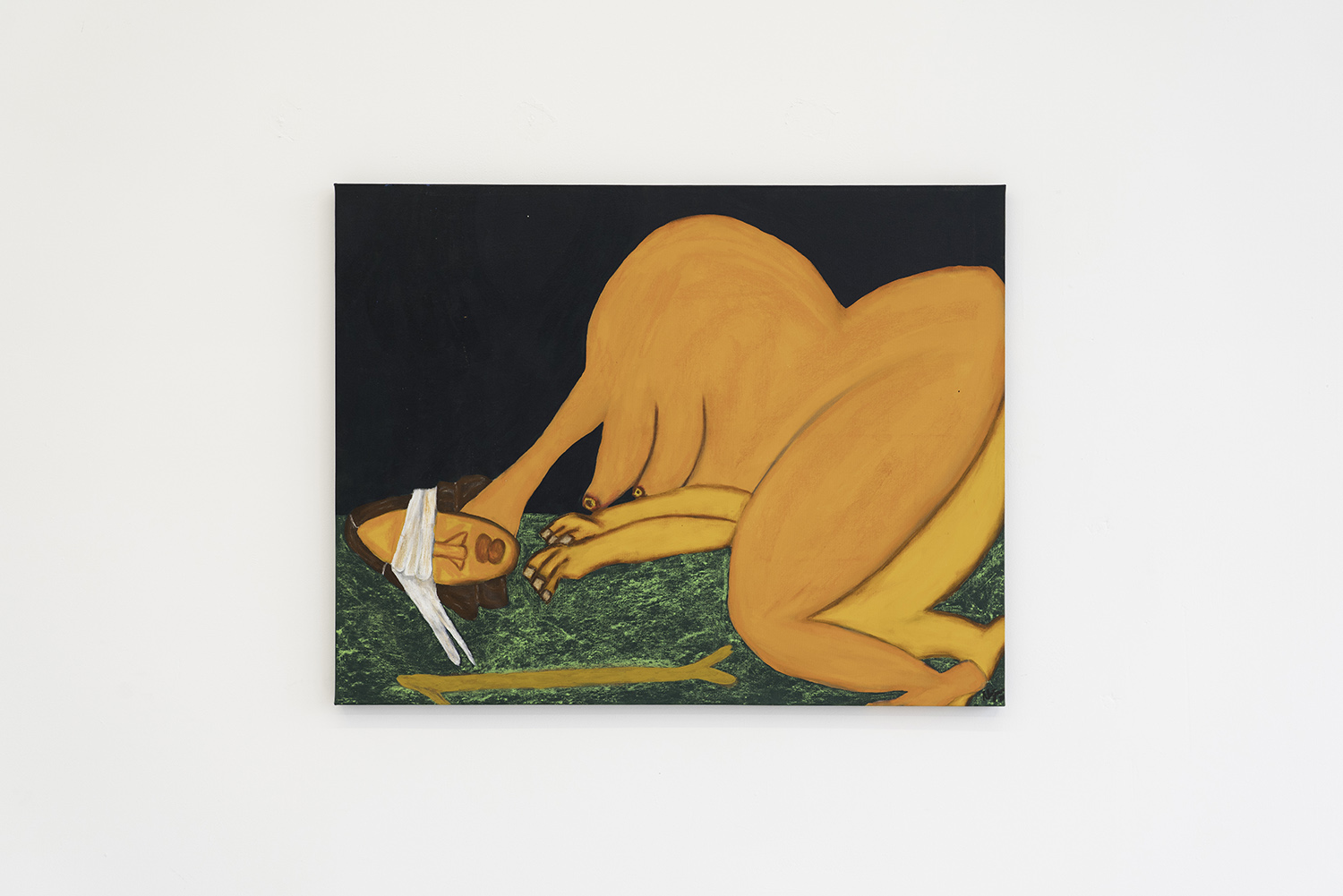

Powerlessness explores the dynamics of power—its presence, absence, and the unawareness of possessing it. In the grand play of the world, men visibly hold power. To prevent women from feeling excluded, they are often led to believe they possess a subtler, more elusive form of power—control over men. This illusion makes it difficult for women to separate their identity from male influence, for in doing so, they risk losing even the perception of power.

The work questions the constructs that bind power to gender, revealing the complexity of agency and dependence.

Najaax Harun, new item, 2024, acrylic and oil pastels on canvas, 66 × 45 cm

From a young age, I questioned the concept of dowry—why it is given to the woman, and why men are the ones offering it. If marriage is a mutual agreement, what is the need for this exchange? As I grew older and engaged in conversations with both women and men, I came to understand that many women see the size of their dowry as a reflection of their honor and social status. Among peers, there is an eagerness to learn how much a friend’s dowry was, as if this figure measures her worth. For men, dowry often signifies power—an indication of financial prowess. Beyond the couple, the woman’s family also plays a role, negotiating the dowry as if bargaining for a prized possession they have nurtured, now seeking compensation that reflects her value. While religion intersects with these practices, my painting does not focus on that aspect. Rather, it offers a commentary on how the community views women as commodities, their worth determined by monetary exchange.

Najaax Harun, Sept. 2024

Najaax Harun, under the mercy of hangool, 2024, acrylic and oil pastel, 100 × 100 cm

The hangool, a traditional tool of Somali nomads, is used both as a walking staff and to protect livestock from predators. However, its historical uses extend beyond these practical functions—it was once a means of controlling women within the household. Though such practices have faded in contemporary times, their echoes persist. The form of the woman in this painting is drawn from the silhouette of the camel, a prized animal in Somali culture, central to life and tradition, symbolized by the custom of offering a hundred camels as dowry. The parallels between women and camels, from a Somali perspective, are striking—both are seen as valuable, yet subject to control. Here, the hangool becomes a metaphor for the enduring force of patriarchy, under which women remain constrained. The honor tied to marriage, shaped by male perspectives, continues to be accepted, often unquestioned, reflecting the complex layers of societal influence still at play.

Catinca Tabacaru Gallery is thrilled to open its new season with two captivating solo exhibitions which bring into focus the standing of women in what is often considered opposing social and political systems: Western and Muslim worlds.

HAGOOGTIR—meaning “unveiling”—reflects Najaax’s resolve to illuminate the obscured realities shaping women’s existence. Committed to breaking the silence that has veiled these issues around the world, Najaax draws on her own experiences as part of the post-civil war generation, witnessing the persistence of outdated norms. Her paintings become a personal mission, shining light on entrenched patterns and provoking introspection. The work stands as a beacon, challenging the status quo and inviting a dialogue that inspires transformation toward a future of authenticity, awareness, and enlightenment.

“My desire to approach the canvas emerged from a profound need to understand and communicate myself to the world, carrying the stories around me.”

Somaliland’s history is a tapestry woven with threads of colonial disruption and post-war reconstruction. British rule reinforced and intensified existing patriarchal structures by embedding stricter gender norms and excluding women from political and economic spheres. As Somaliland emerged from colonialism into the chaos of civil conflict, the imposition of Sharia law sought to unify a fractured society. This shift further entrenched conservative values and the confluence of colonial legacies, wartime upheaval, and religious codification sculpted Somaliland into a society where the hopes and participation of women is largely ignored.

Armed with this personal history of growing up in a country still awaiting international recognition, Najaax’s paintings reveal for us the secret lives of the women around her. Women, whose lives are progressing within, and parallel to, an ever-present patriarchal structure. But, also women who are acutely aware of how their existence is often misunderstood as a cultural norm; how the Western gaze, lacking in historical context or significant cultural understanding, looks upon them as powerless victims. They are anything but victims.

Najaax reveals to us the power, resistance and sexuality of her subjects in her first solo exhibition, HAGOOGTIR | UNVEILING running at Catinca Tabacaru, Bucharest September 26 through November 3, 2024.