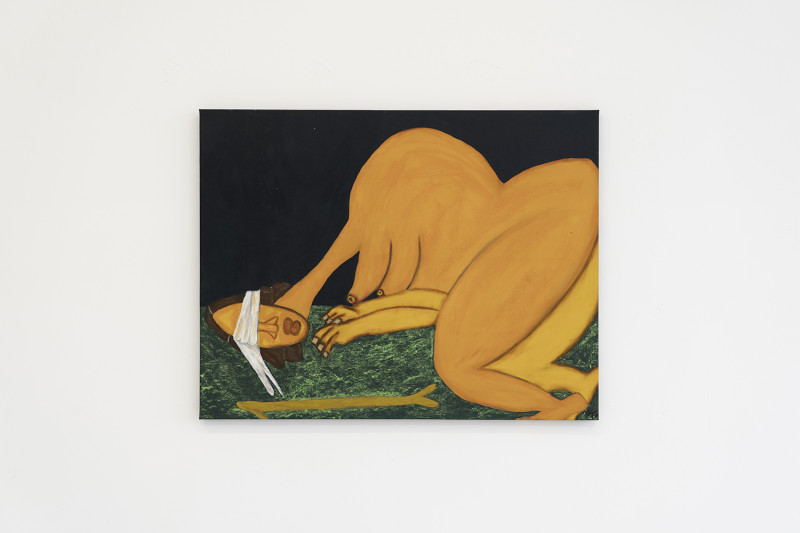

Najaax Harun, under the mercy of hangool, 2024, acrylic and oil pastel, 100 × 100 cm

From a young age, I questioned the concept of dowry—why it is given to the woman, and why men are the ones offering it. If marriage is a mutual agreement, what is the need for this exchange? As I grew older and engaged in conversations with both women and men, I came to understand that many women see the size of their dowry as a reflection of their honor and social status. Among peers, there is an eagerness to learn how much a friend’s dowry was, as if this figure measures her worth. For men, dowry often signifies power—an indication of financial prowess. Beyond the couple, the woman’s family also plays a role, negotiating the dowry as if bargaining for a prized possession they have nurtured, now seeking compensation that reflects her value. While religion intersects with these practices, my painting does not focus on that aspect. Rather, it offers a commentary on how the community views women as commodities, their worth determined by monetary exchange.

Najaax Harun, Sept. 2024