Najaax Harun, powerlessness, 2024, acrylic and oil pastels on canvas, 100 × 100 cm

Powerlessness explores the dynamics of power—its presence, absence, and the unawareness of possessing it. In the grand play of the world, men visibly hold power. To prevent women from feeling excluded, they are often led to believe they possess a subtler, more elusive form of power—control over men. This illusion makes it difficult for women to separate their identity from male influence, for in doing so, they risk losing even the perception of power.

The work questions the constructs that bind power to gender, revealing the complexity of agency and dependence.

Najaax Harun, lost in translation, 2024, acrylic, oil pastels. 100 × 85 cm

Najaax Harun, passing on honor, 2024

acrylic and oil pastels on canvas, 50 × 100 cm

A shadow of a woman passes the mantle of so-called honor to another, embodied in the form of a veil. This act suggests that a piece of fabric becomes the defining measure of a woman’s worth and dignity. The veil, not the woman herself, becomes the symbol of her value, and without it, she is denied the illusion of respect that society bestows upon those who conform. The veil is not merely cloth; it is a mechanism of control, reinforcing the belief that a woman’s honor is external, conditional, and rooted in submission to societal norms

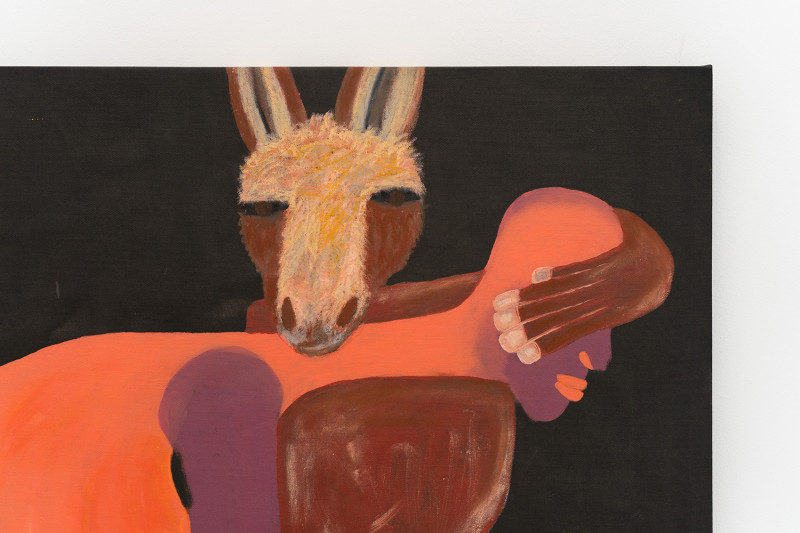

Najaax Harun, straight path, 2024, acrylic, oil pastel, 90 × 110 cm

Straight path draws inspiration from the parallels between guiding a group of humans and leading a group of donkeys.

In my community, to direct a donkey, we affix two cardboard pieces on each side of its eyes, narrowing its vision to the path ahead, ensuring focus, discipline, and a singular direction. This practice, while seemingly mundane, serves as a satirical commentary on how communities not only control animals but also navigate social interactions with one another. In retrospect, I see echoes of this in my own upbringing and education—where, though not literal pieces of cardboard, systems of belief and education shaped and constrained perception, guiding me along predetermined paths

Najaax Harun, Sept. 2024.